Award-winning micro-photos depict stunning details of nature

Honored pix range from a rice weevil and a web of neurons to spindly sunflower hairs

This rice weevil — perched on a grain of rice — came in first place at the 2025 Nikon Small World photo competition.

Zhang You

Through the lens of a microscope, even a dirty windowsill can hold treasures.

The rice weevil (Sitophilus oryzae) is a pest that devours grains and seeds. Seen atop a grain of rice, this glamour shot, above, won first place in the 2025 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition. Zhang You stumbled upon the dead insect while cleaning his house. He captured the rice weevil’s final flight by stacking more than 100 photos taken with a microscope.

Finding a dead weevil with its wings outstretched was lucky. “Their tiny size makes manually preparing spread-wing specimens extremely difficult,” says You. “So this naturally preserved individual is rare.” You’s a member of the Entomological Society of China. (Entomologists study insects.)

He mounted this weevil on a grain of rice to highlight its small size. He hopes the photo can provide insights into the pest’s structure. “To me, a standout work blends artistry with scientific rigor,” he says of the image. It captures “the very essence, energy and spirit of these creatures.”

The perched rice weevil was one of 71 striking photos honored on October 15 in this year’s competition. Here are a few of our other favorites.

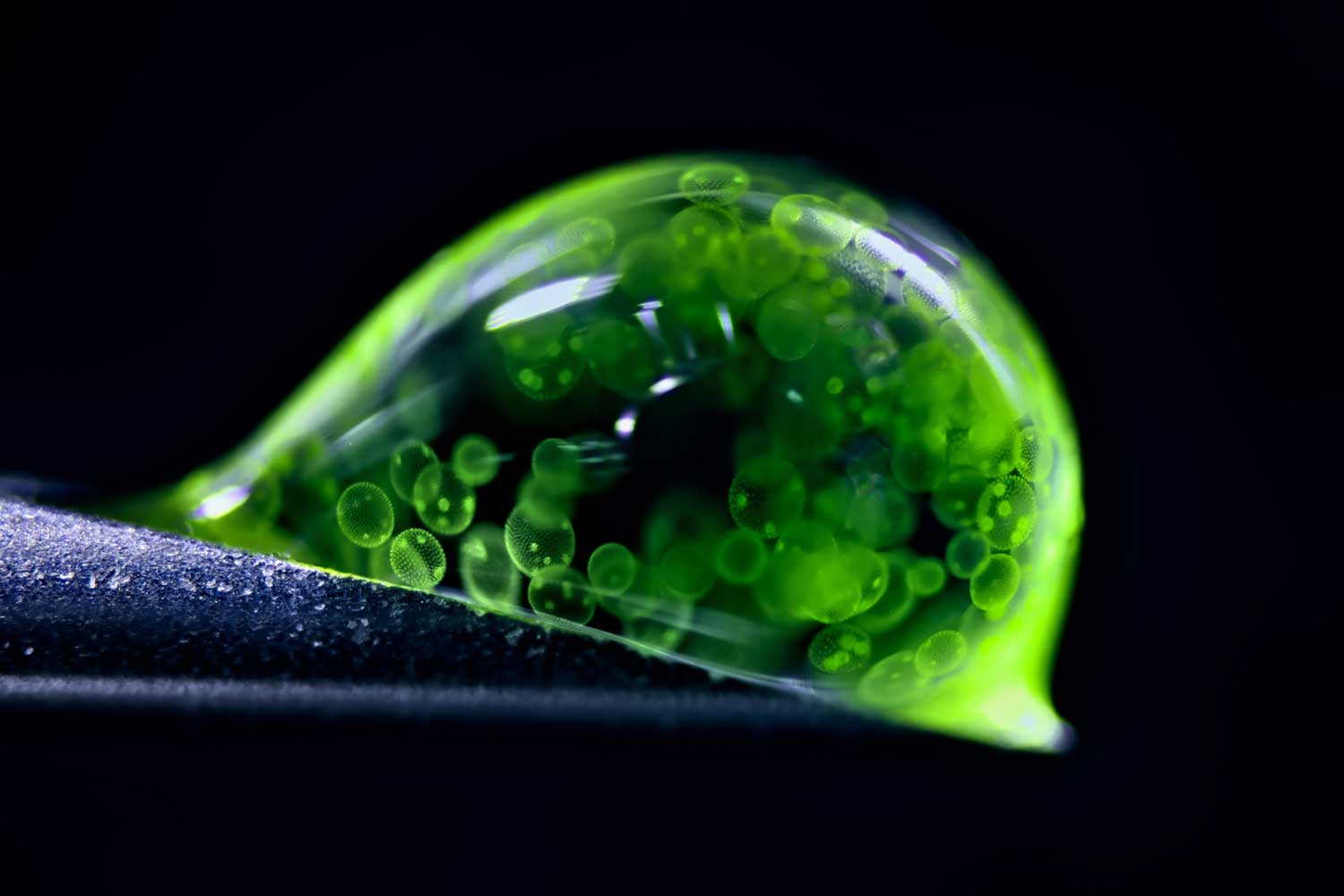

A drop bursting with life

This orb — a water droplet — hosts a multi-celled universe.

Jan Rosenboom photographed hundreds of algae cells moving through the droplet. The German photographer and chemist used LED lights to capture the image. He also used a 50-year-old microscope, one that he purchased at age 14.

The algae here (Volvox) bloom in freshwater ponds, lakes and puddles. Their oval-shaped cells are outlined in green. The brighter green polka dots inside the outlines are young algae forming within each mother cell.

The droplet rests at a precarious angle on the tip of a syringe. Rosenboom spilled more than 20 droplets before snapping this second-place photo.

This image shows how much life can exist in a single drop of water, Rosenboom says. He hopes it helps people understand that even small worlds have biodiversity worth protecting.

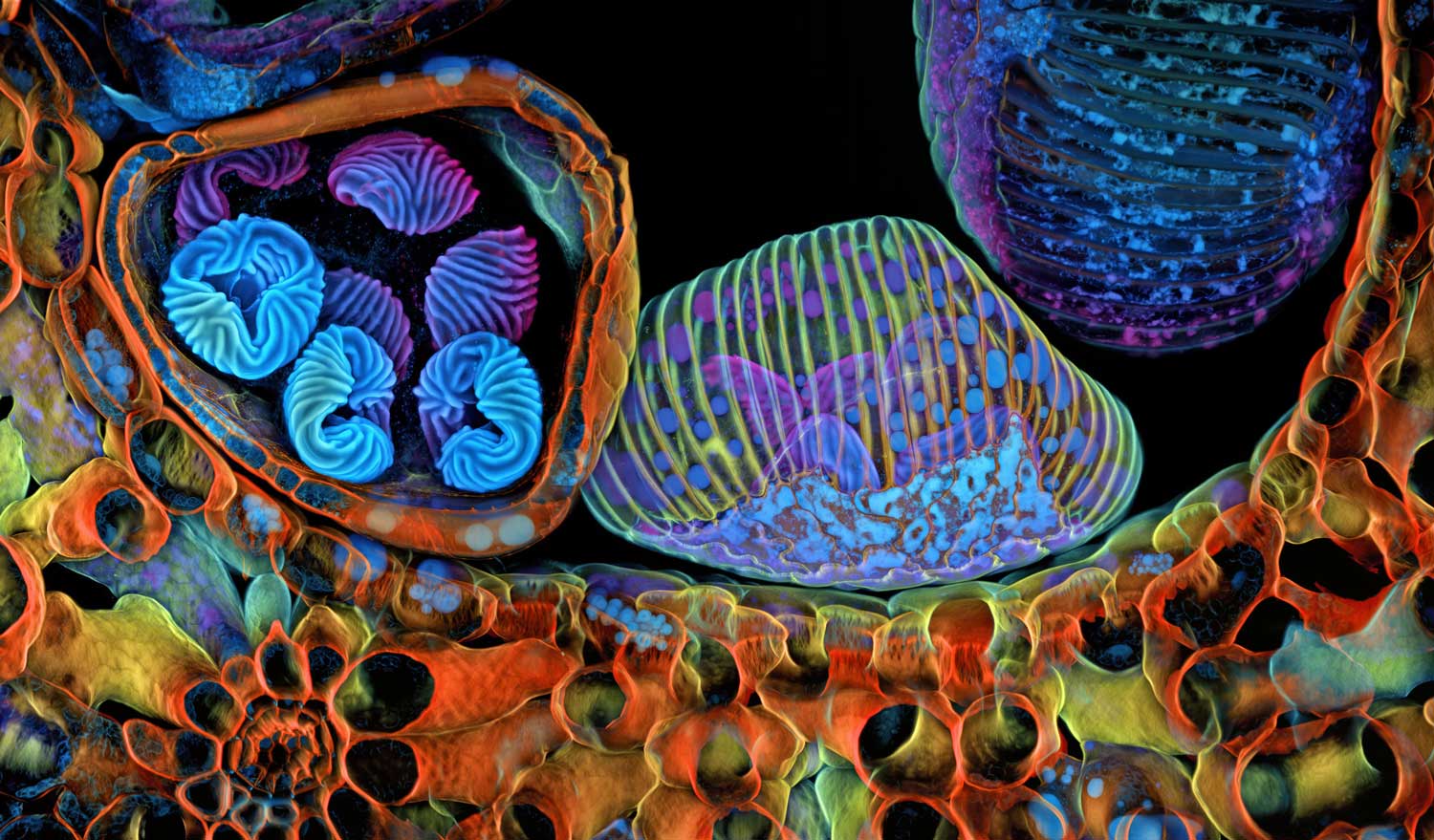

Fluorescent ferns

Kaleidoscopic pop art? No, these are the spores of a humble fern, shown in vibrant detail. Spores are cells that some plants, fungi and bacteria use to reproduce. Like seeds, they’re often spread by the wind or small animals.

Igor Siwanowicz lit these here using fluorescent lasers in a confocal microscope. This type of microscope shines lasers at a specimen to get rid of out-of-focus light. One advantage: It produces crisp images.

This image shows three podlike structures. Known as sporangia, these structures are where a fern’s spores grow. Siwanowicz sliced the pods in half with a small razor. This revealed what was inside them. The left pod holds spores with brain-like shells. The center pod remains unopened. And the right pod is empty. It likely burst and dropped its spores while he was prepping for the photo, Siwanowicz says. The frond tissue of the surrounding fern (Ceratopteris richardii) is orange.

Siwanowicz studies anatomy at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus. That’s in Lansdowne, Va. He especially enjoys the chaos of the image, which won fifth place.

“Microscopy images are very abstract and sometimes alien-looking,” says Siwanowicz. “They’re confusing. But sometimes confusion creates this urge to find out more.”

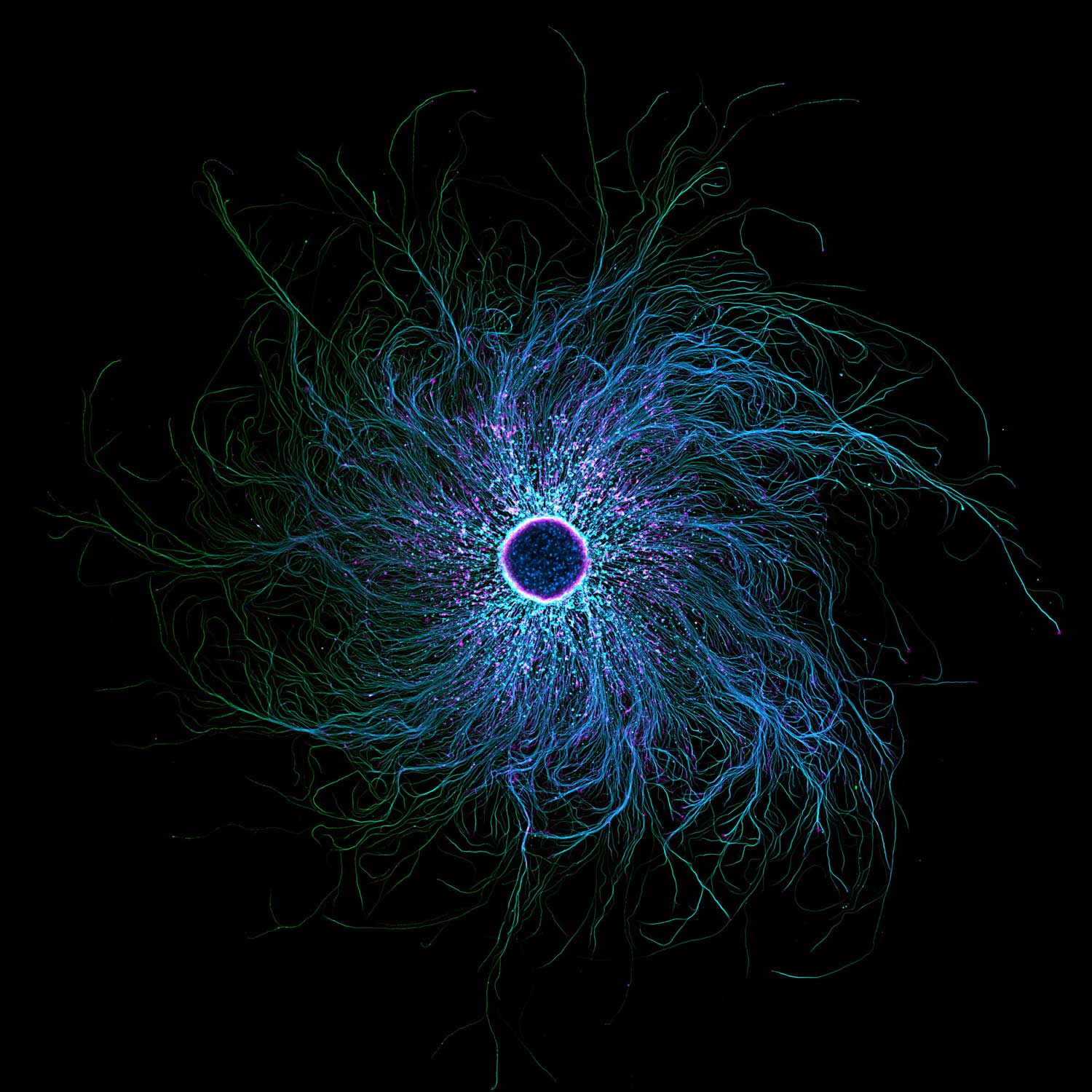

Sprawling neurons

This web of neurons may resemble the iris of an eye. But their spindly structures are designed to enhance touch, not sight.

Those wispy, rootlike arms help people sense what’s around them, says Stella Whittaker. A biophysicist, she studies the structure of sensory neurons. She took this photo while working at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Bethesda, Md.

Her image displays the swirling branches of a type of neurons found in our arms, legs and spine. Whittaker colored the image with fluorescent molecule tags. These bind to proteins in the neurons. When the microscope’s laser hits the tag, it causes the neurons to light up.

The pink, speckled dots highlight actin. It’s a protein that helps muscles contract. The blue and green bits are microtubules. These act as highways for transporting organelles in and out of cells. At the center, 10,000 cells group together.

Studying the structure of neurons can help researchers understand how diseases develop in the brain, Whittaker explains. She’s now earning her Ph.D. at Weill Cornell School of Medicine in New York City.

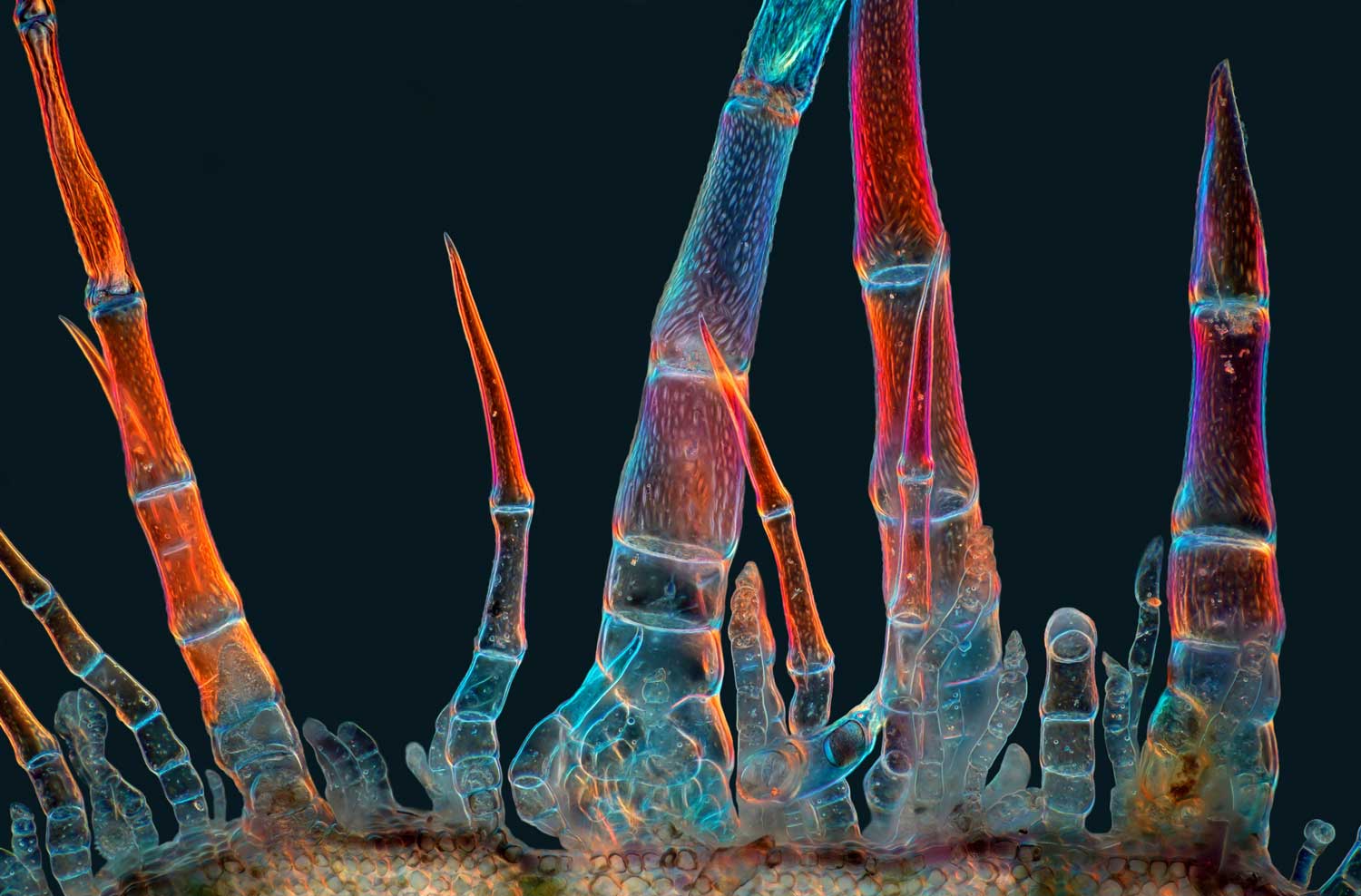

Hairy forest?

This may look like a chorus line of insect legs reaching for the sky. In fact, these are trichomes (TRY-kohms). Such super-tiny structures protrude from the surface of many plants. They provide some sort of physical or toxic chemical defense against pests or disease-causing agents.

The ones shown here were found on sunflowers. Marek Miś couldn’t resist sticking slices of this bristly tissue under his microscope. Miś is a photographer and longtime nature-lover based in Poland.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

He collected the trichomes from a bloom’s stem. He then lit them up with light passed through a homemade polarizing filter. Only light waves wiggling at certain angles could pass through the filter. That changed the hue these trichomes reflected.

The mesmerizing magentas and blues in the final image are stitched together from more than 100 photos. They highlight how trichomes come in a variety of shapes and sizes.

“Trichomes are not all the same,” Miś says. “The sunflower, already a beautiful plant in itself, hides additional beauty that cannot be seen with the naked eye.”

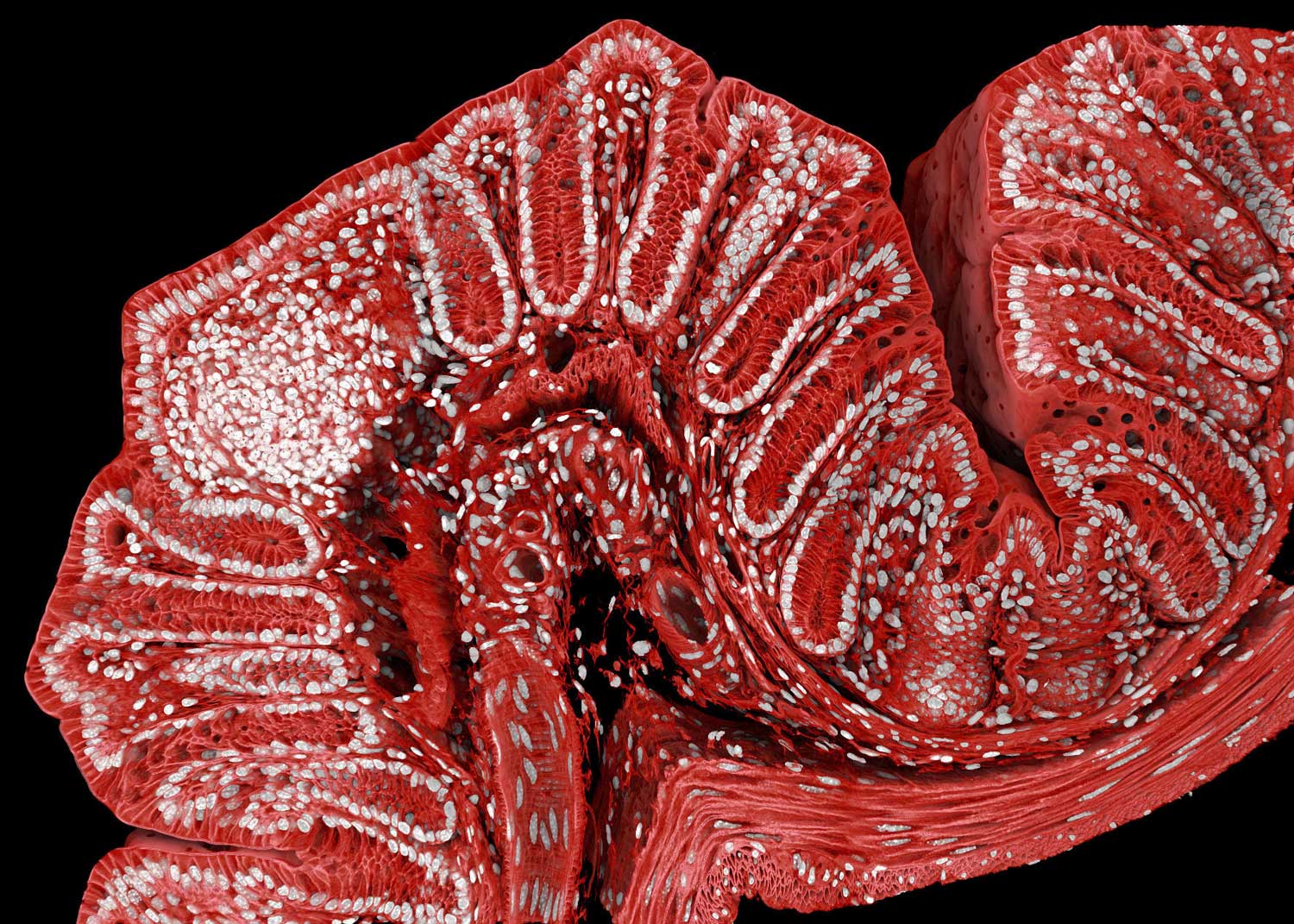

Tiny intestines

What may resemble the decorative applique on some fashionable gown is actually the closeup of a mouse colon. It certainly brings glamour to the gut.

Marius Mählen is part of a team that wanted to learn how tissues grow. “If you figure out the rules by which healthy tissue forms,” he explains, ”then you will also start to understand why cancer tumors, for example, form very weird-shaped tissues.”

Mählen is a biologist at the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research. That’s in Basel, Switzerland. There, his team studies organelles in mouse cells. Their goal is to see how diseases, such as colon cancer, develop.

Over the course of one weekend, the team took 600 images of one mouse colon. They used a confocal microscope, then stitched the images together to create the final image.

By adding antibodies and dye, Mählen and his team marked the cells in the image with different colors. The nuclei of the cells appear in white. The cell membranes are now red. And the white clump toward the left marks a horde of immune cells scouting for invaders.