Scientists created human egg cells from skin cells

This technique could one day help people who lack reproductive cells have children

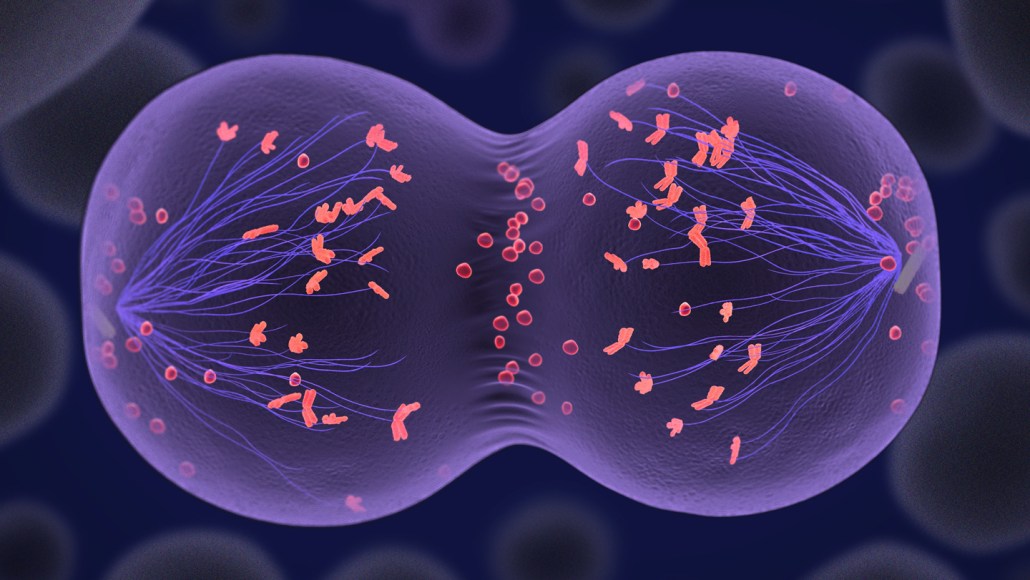

In an experiment, scientists were able to craft new egg cells with the DNA of a specific person. They started by dropping that person’s DNA — from one of their skin cells — into an empty donor egg. Then, the scientists had to get the modified egg to boot out half of its 46 bundles of DNA, or chromosomes. The egg did this in a process called meiosis (illustrated here).

Tim Vernon/Science Source

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Every human being starts with the fusion of two cells: an egg cell from one parent and a sperm cell from the other. But for a variety of reasons, two parents may not have both the egg and sperm needed to make a baby. That has led some scientists to wonder if they could make an egg or sperm cell with a parent’s DNA from some other type of cell in their body. Now, a new study brings that one step closer to reality.

In the experiment, researchers caused human skin cells to produce egg cells. Some of those eggs were able to give rise to early human embryos.

Researchers shared their findings September 30 in Nature Communications.

Such tech may one day help women without healthy eggs to have children. That may include older women, or those who have been through cancer treatments. Same-sex male couples may also be able to use the technique to have a child that’s related to both of them, says Paula Amato. An expert in reproductive medicine, she works at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

The technique is not yet ready to help people have children. It’s still “too inefficient and high risk,” says Katsuhiko Hayashi. A researcher at the University of Osaka in Japan, he did not take part in the new work. But his team has reprogrammed tail cells from two adult male mice into eggs and sperm. Those reprogrammed cells gave rise to healthy mice that had two fathers. And these pups grew up to have offspring of their own.

Airdropping DNA

Researchers have already produced eggs and sperm for many types of animals. But producing human eggs and sperm has proven difficult.

Amato’s group started with a donated human egg cell. They first removed the nucleus — the part with DNA — from that egg. Then, they replaced the donor egg’s nucleus with a one from a skin cell. (In the future, such a skin cell would come from the intended parent for the egg.)

But there was a problem.

Nuclei from most cells in the body, including skin cells, contain 46 bundles of DNA called chromosomes. But an egg cell has only 23 chromosomes. Why? Because when an egg and sperm cell meet, they each bring 23 chromosomes of their own from the parent. When they fuse, this egg and sperm produce a new cell. Called a zygote, it now has all 46 chromosomes needed to build a new human.

In short, the donated egg with the transplanted nucleus had twice as many chromosomes as an egg should have. To fix that, the researchers used a chemical called roscovitine. It coaxed the modified eggs to throw out some of their extra chromosomes when fertilized by sperm.

Mixed results

Some of the fertilized eggs made early human embryos. Many did not.

“That’s probably, we think, because they had an abnormal number of chromosomes,” Amato says. The failed eggs kicked out half their chromosomes, on average. But not the right half.

None of the embryos were allowed to grow for longer than about six days. Many stopped developing at earlier stages.

No embryo ended up with the right sets of chromosomes. So none would have grown into a healthy human. For instance, one embryo had 48 chromosomes instead of 46. That embryo had all 23 chromosomes from the sperm. But it had 25 from the skin cell. Some of those chromosomes had two copies. Others were missing entirely.

“It was not the outcome we wanted,” Amato says. “But it was more proof-of-concept. ‘Hey, we can kind of make this process happen now.’”

What’s next?

The team is now working to craft eggs with the right sets of chromosomes. But Amato suspects it will be at least a decade before the technique could be tested in clinical trials. Even then, such trials would probably not take place in the United States, Amato notes. U.S. law forbids tweaking the DNA of human embryos.

One drawback to the new technique: It requires donor egg cells, Hayashi notes. Reprogramming cells as his team has done does not need egg cells to make other egg cells. Still, he says, “this technology has made a significant breakthrough.” And, he predicts, “new technologies will stem from this achievement.”