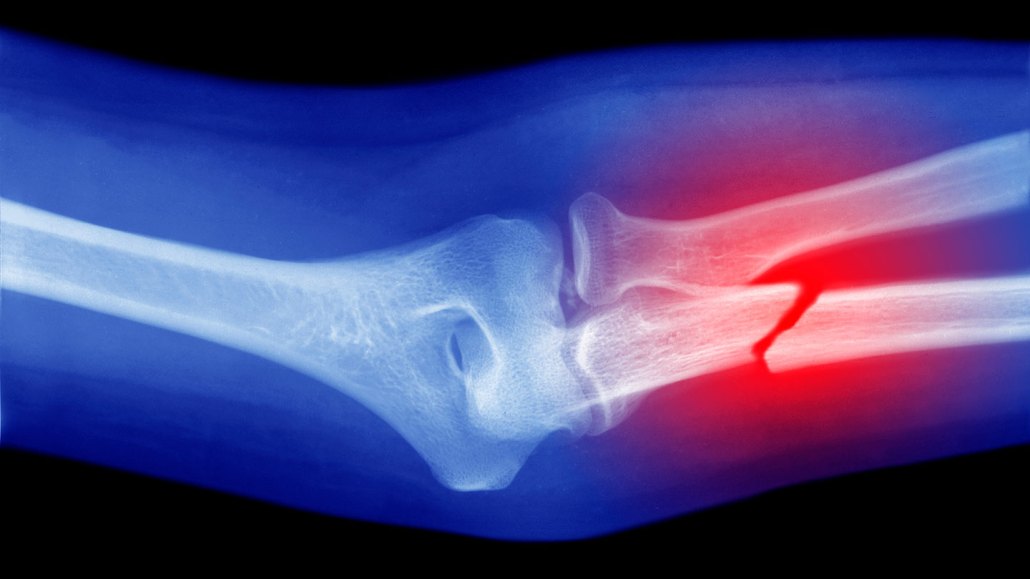

A modified glue gun squirts a material to help heal broken bones

The handheld device applied antibiotic grafts onto fractured bones in rabbits

A handheld 3-D printer might someday print bone grafts directly onto fractures. Researchers prototyped the idea with a modified glue gun. They included antibiotics in the material to ease healing.

Peter Dazeley/The Image Bank/Getty Images

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Payal Dhar

A repurposed glue gun has helped repair broken bones in rabbits. Instead of a regular glue stick, it melts a material that helps bones heal.

Some breaks in bones need a little help to mend. So surgeons sometimes take a bit of bone from elsewhere in the body to make a patch called a graft. Or they can use a synthetic — human-made — material that mimics bone.

Synthetic grafts are often 3-D printed. Usually, X-ray scans and measurements of injuries are needed to make sure the graft will fit just right. Designing and making the graft takes time and can delay repairs.

But the glue gun method doesn’t require images of the fracture. And it doesn’t need any special graft design. The handheld device can simply squirt the graft material right onto a break.

The idea was to design a printing system that could be easily used in operating rooms, says Jung Seung Lee. He’s a biomedical engineer at Sungkyunkwan University. That’s in Seoul, South Korea. Compared with regular bone grafts, he says, this system can save time, cost and complex procedures.

The printing device holds sticks of a specially made “bioink.” It’s safe to use in the body. It consists of two compounds commonly used for 3-D printing implants. One, hydroxyapatite, is a mineral found in bones. The other is a body-safe plastic called polycaprolactone, or PCL. That’s included to support new bone as it grows. In an implant, it “gradually degrades in our body over months,” Lee says. Over time, newly grown bone will fill in as the graft breaks down.

The ratio of the two compounds in the bioink determines the material’s strength and stiffness. So the researchers can tailor the mixture for each use. They also added antibiotics into the bioink to prevent infections.

Crafting grafts

Like the glue sticks used for crafting, the bioink fits in the handheld printer. It can be squeezed out where it’s needed. But regular hot glue guns work at temperatures far too high for living tissues.

So the researchers modified their glue gun to work at lower temperatures. They also adjusted the tip for better control. Thanks to the low melting point of PCL, the bioink can be applied at about 60° Celsius (140° Fahrenheit). It cools to body temperature within 40 seconds. The whole process takes just a few minutes.

Lee’s team tested the printer and bioink on broken leg bones in rabbits. Another set of rabbits got a material called bone cement, which is used to attach implants to bones. The rabbits that got the bioink had better healing and regrowth of bone tissue. And the animals showed no signs of infection during the 12 weeks after surgery. The team shared its results September 5 in Device.

For now, the printer is still a proof-of-concept for people. Lee aims to develop it into a multi-use printing system. For instance, it might apply chemicals that promote healing during surgeries. But first, researchers will have to do more studies to make sure the technology is safe. They’ll also need to figure out how to disinfect the device between uses.

There may be other limitations. “The high temperature of the extruded material is likely to stress or kill the cells,” says Deborah Mason. She’s a molecular and cell biologist at Cardiff University in Wales. She wasn’t involved in the study. Lee’s team is working to modify the tip of the device. That could help the bioink cool more quickly after extrusion.

In the future, this sort of device could help surgeons with more complex repairs, suggests Nieves Cubo-Mateo. She’s a biomaterials engineer at Nebrija University in Madrid, Spain. She wasn’t part of the study.

But there is a long way to go for that to happen, she says. The printer would need to work with other tools that surgeons use. Those include imaging technologies and robotic devices used during surgeries. That would take the new device beyond just a “defect-filler,” she says. Someday, it could be a “bone printer pen” useful for many types of surgeries.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores