Scientists caught a black hole ringing like a bell

It produced ripples in spacetime — the clearest ones ever observed

Two black holes spiraled around each other before combining into one. Here the black holes are shown as two black dots. This is a computer simulation of the gravitational waves (white and blue) released by that merger.

Deborah Ferguson, Derek Davis and Rob Coyne/URI, LIGO, MAYA Collaboration, simulation performed with NSF's TACC Frontera supercomputer

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

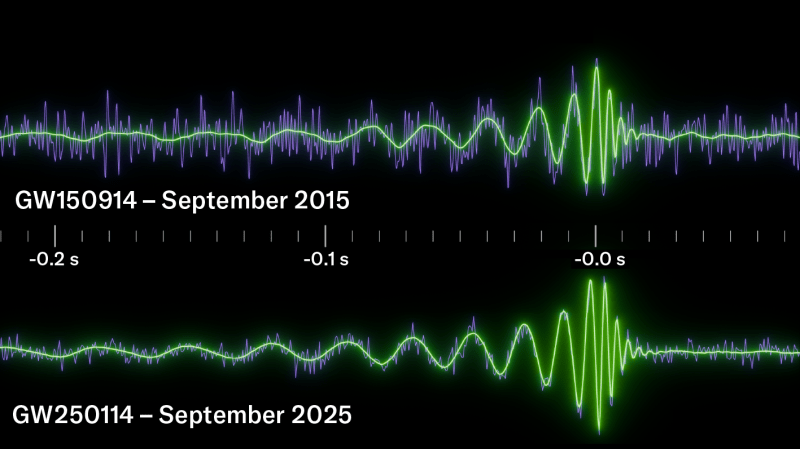

A ringing black hole made ripples in spacetime. Spotted for the first time in January, these ripples are the clearest yet observed.

Researchers reported detecting the signal in the September 12 Physical Review Letters.

Such ripples are known as gravitational waves. They develop when massive objects rapidly accelerate in the cosmos.

The newly discovered ones were born when two black holes merged. The pair formed one larger black hole that now rang like a struck bell. It emitted gravitational waves as its vibrations faded.

Scientists had predicted this, based on general relativity. That’s a theory of gravity. It describes how mass bends spacetime (which then gives rise to gravity). Gravitational waves stretch and squeeze spacetime as they pass by. General relativity also predicts that extremely compact objects — black holes — can form. Around them, spacetime will bend so much that nothing can escape.

The new finding confirms that these and other rules of general relativity apply to black holes.

Like a bell

The newly reported spacetime ripples had cut through background noise. And they did that better than any previous gravitational waves.

Just hearing a bell can tell you if it’s big or small, says Katerina Chatziioannou. A physicist at Caltech in Pasadena, Calif., she worked on the new study. “The frequencies that an object makes when you strike it are unique to it,” she says. For a bell, those frequencies correspond to different pitches, or sounds. The bell’s size and shape determine what sounds it will make when struck.

“The same thing is true with black holes,” she says.

Like bells, black holes ring with a fundamental pitch. Both also ring at other frequencies, known as overtones. Those overtones fade away more quickly than the fundamental. For the newly reported merger, both the fundamental and the first overtone were detected.

LIGO (short for the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) detected the gravitational waves. LIGO is made of two detectors — one in Hanford, Wash., the other in Livingston, La.

LIGO’s measurements matched something called a Kerr black hole. That’s the prediction for how a spinning black hole should behave. It’s based on a solution to the equations of general relativity. (New Zealand mathematician Roy Kerr first worked out that solution back in 1963.)

Similar tests have been tried before with gravitational-wave data. But this is the first time an overtone has been detected so clearly. That’s necessary for this type of test, Chatziioannou says.

The team also considered a concept called the area theorem. It was developed by physicist Stephen Hawking in the 1970s. It states that the surface area of a black hole can grow over time — but not shrink. The newly formed black hole had a surface area larger than the sum of the two original ones. That agrees with this rule.

An earlier black-hole merger also seemed to agree with Hawking’s area theorem. But the latest, clear signal gives a more definitive match.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores